The Beast by Eddie Perfect. Presented by Ambassador Theatre Group Asia Pacific and Red Live at Sydney Opera House Drama Theatre, July 27 – August 21, 2016.

Directed by Simon Phillips.

Designers: Set and Costume by Dale Ferguson; Lighting by Trent Suidgeest; Composer – Alan John.

Cast: Heidi Arena – Sue; Alison Bell – Marge; Christie Whelan Browne – Gen; Peter Houghton – Skipper / Mansitter / Vigeron / Farmer Brown; Rohan Nichol – Simon; Eddie Perfect – Baird; Toby Truslove – Rob.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

July 31

I shouldn’t read the Director’s Note before the show, especially when he writes of “acute social comedy” as if it’s a disease, and goes on to “add to it a sense of iconclastic extremity which puts [Eddie Perfect] in the company of Joe Orton, Martin McDonagh or even Ionesco.” How pretentious!

Except that it’s sort of true. The killing of the fatted calf, which provides the completely over the top funniest end of Act 1 of any play I’ve ever seen, does have a weird connection to Eugene Ionesco’s Rhinoceros. In that play, everyone turns into green rhinoceroses, except Berenger who bravely stands against the trend. “I am not capitulating!” are his last words.

The Beast also deals with conforming to norms, or refusing to do so, or being too weak not to, and there are political implications when it comes to the question of ethical farming, just as people turning into rhinoceroses represented those who had gone along with Nazism. But Perfect’s play is more complicated than Ionesco’s as he brings three married couples together, exposing their middle-class predilections, hypocrises, secrets, and politically correct naivety.

Perfect’s work is also more absurd than Ionesco’s in the sense that Ionesco has a single through-line, even though it takes a little while to become apparent after the first rhinoceros inexplicably kicks up the dust in the French village square. In The Beast there are bits of throughlines going all over the mental landscape until the very end, when Farmer Brown puts everything into its proper context and they all eat carrots.

The Beast is also equivalent to Rhinoceros in another way. Ionesco’s play is very specifically French, in location and culture. Perfect is Melbourne through and through and his play is specifically Australian, in location and culture. Specificity is a strength in both plays, oddly enough, because it makes for universality of significance. Even though extreme comic acting exaggerates characters, Perfect’s are each recognisably Australian, as Ionesco’s are French. This works as in the dictum “act local, think global”.

I’m writing maybe a bit too globally here, but I can promise that even though I haven’t told you much about what actually happens in The Beast, that’s because it’s better for you not to know too much. The comedy is over-the-top extremely funny because of the unpredictable surprises that Eddie has perfected as a stand-up comedian. So get stuck into The Beast and you’ll see what I mean.

|

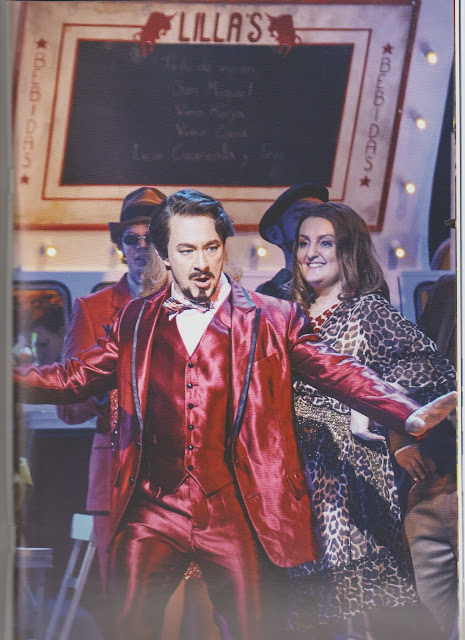

| The Calf |

|

| Eating carrots |

©Frank McKone, Canberra