The Tempest by William Shakespeare. Bell Shakespeare directed by John Bell; set and costume designer, Julie Lynch; lighting designer, Damien Cooper; composer, Alan John; sound designer, Nate Edmondson; movement director, Scott Witt. The Playhouse, Sydney Opera House, August 19 – September 18, 2015.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

August 29

Only one other production of The Tempest has inspired me as much as John Bell’s farewell to his career as artistic director and founder of Bell Shakespeare. This was Rex Cramphorn’s “1972 Performance Syndicate production of The Tempest [which] received critical and popular acclaim, being remounted and taken on tour until 1974.” It’s an irony of history that Cramphorn’s later production of The Tempest in 1991 was his last show before his untimely death in November that year.

There seems to be something magical in the divergences and points of contact in the histories not only of John Bell and Rex Cramphorn, but even for me. Our births were very close (1 November 1940, 10 January 1941 and 9 January 1941 respectively), though far apart in Maitland, Brisbane and the UK. We each were influenced by choreographer and dance-drama teacher, the inimitable Margaret Barr, briefly in my case at summer schools, as his teacher at NIDA for Rex and as his colleague when John taught at NIDA.

I attempted a few dance classes with Margaret Barr, and remember her home as light, white, almost bare of furniture, spotless, pure and simple. I began my 20 year drama teaching career at Hawker College, Canberra, in 1976, with a production of The Tempest, keeping in mind my image of Margaret Barr and Rex Cramphorn’s production, keeping the action within a circle, enclosed only by loose unadorned material. And so it is for John Bell’s production all these years later.

In the tradition of Margaret Barr’s teaching, both Cramphorn and Bell focus on movement of the actors in open space, creating an island of dancing magic – sometimes heavy on the ground, sometimes up and light yet powerful, often ethereal and invisible, yet audible – or, in contrast, silent. This is The Tempest that was also William Shakespeare’s most original and last major work.

It was the creation of a spirit world that had inspired me about Cramphorn’s work. It was a world of philosophic enquiry, where the island became the universe, a place of wonder and mystery. It was this theme that my late teenage students took up enthusiastically, with an image of a huge eye painted high on the rough hessian backdrop, observing all silently, as if from a different universe.

Bell’s production keeps the same feel and the same philosophical implications, but blends in the complexity of ordinary reality. Though Cramphorn (and I) had kept all our actors in the circle on stage throughout, as if there were no other place to be, even for those not active in the scene, Bell used the circle as an ever-changing space into and out of which characters come and go, as if the rest of the island is concretely out there somewhere, while the spot we see shifts from place to place – entirely in our imaginations, with nothing more than wind moving the surrounding material drops, a rope or a log, or no more than the characters’ costumes to tell us where we are.

The effect is to add a layer of understanding to those previous productions, anchored as they were in the 1970s. For me, and I suspect for Rex Cramphorn, influenced so much by Jerzy Grotowski, the freedom of the magical world to explore the unknown was where we needed to go. We were escaping philosophically, perhaps. But the new world order today requires us to come to grips with strategic thinking – as indeed it was in Shakespeare’s time as absolute monarchy was beginning to be taken down, at first by extremist Puritans, until over the next centuries a reasonable form of democracy could evolve. Shakespeare is described in John Bell’s director’s notes as “to have been a remarkably competent businessman and one celebrated by those close to him for his witty, mild and affable companionship”. The very kind of democrat we would all hope to see – and to be.

So in Bell’s production, Prospero is realistically getting a bit past it, and at times is aware that he can’t keep his powers up to the mark. At 74 I find I have the same problem, and perhaps John Bell feels a bit the same way. I asked him if leaving the task of directing Bell Shakespeare, the Company, was to be free in particular of Responsibility (though he is continuing to work, as an actor in Ivanov with Belvoir next month). “No more applications for funding grants,” was his reply. And there he was, as director of The Tempest, in the second week of the run, still watching and making notes for cast and crew.

My notes say that the casting is excellent, the set and costumes brilliant, the lighting, sound and music composition wonderful, and the movement exciting and telling: the balance between fantasy and reality, or rather the fact that both exist at one and the same time, is made in the movement design and the capacity of the actors to work as dancers – and singers – while completely grounded in their characters.

You may not think you are seeing dance for the most part, since the choreography is of symbolic or natural seeming movement. But watch this perfect apparition of Ariel, played with such grace and strength by Matthew Backer. Watch the two drunken clowns, Trinculo and Stephano – Arky Michael and Hazem Shammas, who also amazingly play Sebastian and Antonio – to see what I mean about choreography. But especially watch the one and only woman in the cast (the others – Caliban's mother Sycorax and Prospero’s wife – die before the play begins).

Eloise Winestock shows us Miranda as the girl brought up in the wild – she hisses at Caliban with animal ferocity. Now the hormones of developing sexuality lock her onto the quite proper young man, Ferdinand. Felix Gentle is exactly the right name for this actor, and his Ferdinand is just as amazed at Winestock’s Miranda as she is by him.

I would have presented Caliban, I think, as much more ugly or wild-looking, but I can see why Damien Strouthos was given a less animal-like hair cut, but one still representing rebellion. It makes him a genuinely serious threat to Miranda’s safety, which Prospero must defend, while we also realise that Caliban is justified in hating Prospero, in parallel to Ariel’s position – though Ariel is more like an indentured labourer, while Caliban is enslaved.

Finally, Prospero’s awareness of his own ageing frailty explains how he can step out of the fantasy and speak directly to us, asking us to free him from his responsibility as an actor. This speech, especially under Bell’s direction, places Shakespeare centuries ahead of his time in theatre history – beyond Bertolt Brecht even. We see this level of sophistication currently in the ABC’s The Weekly, in the relationships between Charlie Pickering, Tom Gleeson, Kitty Flanagan and the studio audience, as well as with us watching our screen at home. If we thought Shakespeare is no longer relevant after 400 years, think again on Prospero’s final speech.

Which ends “Let your indulgence set me free.” And so be it for John Bell, except that it’s no indulgence on my part. Bell writes in his program notes “Prospero is a dreamer and is a disastrously ineffective leader. He prides himself on being a humanist scholar, but in fact governs through terror, tyranny and the employment of dark forces. Shakespeare, on the other hand, seems to have been....” I think the evidence, in this production of The Tempest, proves that John Bell is more like Shakespeare than Prospero, and so thoroughly deserves his freedom.

Links:

Ian Maxwell in Australian Dictionary of Biography, at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/cramphorn-rex-roy-15453

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Bell_%28Australian_actor%29

Garry Lester in Australian Dictionary of Biography, at

http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/barr-margaret-14855

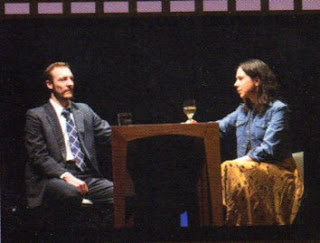

Photos by Prudence Upton

|

| Matthew Backer as Ariel, Brian Lipson as Prospero |

|

| Brian Lipson as Prospero, Eloise Winestock as Miranda, Damien Strouthos as Caliban |

|

| Damien Strouthos as Caliban |

|

| Eloise Winestock as Miranda, Brian Lipson as Prospero |

|

| Thunder and lightning. Enter Ariel, like a harpy |

|

| Eloise Winestock, Arky Michael, Haxem Shammas as Spirit Shapes Brian Lipson as Prospero |

|

| Felix Gentle (Ferdinand) and Eloise Winestock (Miranda) in rehearsal |

|

| The Drunks in rehearsal Arky Michael as Trinculo, Hazem Shammas as Stephano, Damien Strouthos as Caliban |